Happy Halloween!

We know that your amygdala is involved in detecting and responding to risk. As is often the case in neuroscience, researchers have learned a lot about the function of the amygdala by observing patients whose amygdalae (we have two – one in each hemisphere) were inactive due to damage or surgical removal. Without an active amygdala, one is constantly in harm’s way, unable to detect threats and avoid risks.

How would your behavior change if your amygdala were inactive?

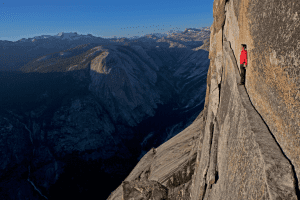

He is constantly asked, “Aren’t you afraid you’re going to die?” Neuroscientist Jane Joseph attempted to answer that question by scanning Honnold’s brain using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) while he was shown shocking and scary images. She wondered if she would discover that he didn’t have an amygdala, but what she found was even more unusual. His amygdala was intact, but not reacting. While a (fellow climber) control subject’s amygdala “lit up like a Christmas tree” when viewing the images, Honnold’s remained quiet. Zero amygdala activation. That would explain his seeming fearlessness. But it is an anomaly to have a normal amygdala with no activation.

All neuroplastic change comes from consistent and persistent effort. The proactive listening, multi-sensory input and movement involved in iLs programs stimulate and integrate neural networks. As our friend Norman Doidge puts it in his book The Brain’s Way of Healing, this is because “mental activity is not only the product of the brain but also a shaper of it.”

Read more about how iLs works to reshape the brain.

You can read more of Alex Honnold’s story in the terrific article from the journal Nautilus.

© 2025 Unyte Health US Inc.

© 2025 Unyte Health US Inc.